European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has announced the Commission wants to develop a new Ocean Pact in order to ensure coherence across all policy areas linked to the ocean. The EU Ocean Days were a good occasion to seek inputs from different stakeholders into the on-going discussions within and across the institutions at different levels.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has announced the Commission wants to develop a new Ocean Pact in order to ensure coherence across all policy areas linked to the ocean. The EU Ocean Days were a good occasion to seek inputs from different stakeholders into the on-going discussions within and across the institutions at different levels.

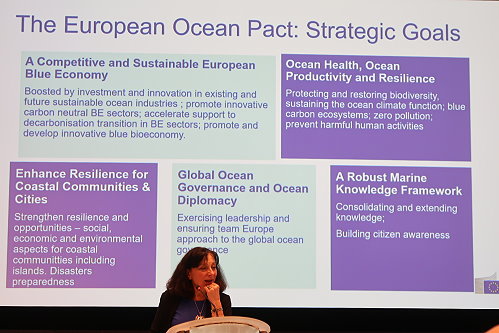

The agenda has the elements necessary, though it may sound at first glance as just another wish list when confronting it with some of the sobering ground truths: Ensure a healthy and productive ocean by protecting biodiversity, all the while boost the EU’s sustainable blue economy. Expand the EU’s marine knowledge framework that should underpin these efforts together with the reinforcement of international ocean governance for developing resilience and opportunities for coastal communities. Knowledge and the resilience of coastal communities are intended as cross-cutting issues.

Charlina Vitcheva speaking both on behalf of Commissioner Costas Kadis and in her function as head of DG MARE emphasised that as a result of the political guidelines of the new Commission it was important to collect views, experiences and efforts across Europe and beyond in a broad brain storming process. That would help underpin to put the ocean firmly on the political agenda with a recognition of the enormous scale of the ocean economy and a desirable investment of almost €60 billion per year.

According to Charlina Vitcheva, the Ocean Pact should ascertain a commitment with strategic goals ranging from competitiveness for the blue economy in the region, restoration of ocean health, productivity and resilience, strengthened diplomacy and global ocean governance, all enabled by a robust marine knowledge framework.

According to Charlina Vitcheva, the Ocean Pact should ascertain a commitment with strategic goals ranging from competitiveness for the blue economy in the region, restoration of ocean health, productivity and resilience, strengthened diplomacy and global ocean governance, all enabled by a robust marine knowledge framework.

MEP Christophe Clergeau, Chair of the SEARICA Intergroup in the European Parliament (EP), took a prompt from Charlina insisting to go beyond aspirational talks. He admonished that none of the top political leaders was present casting doubt on the real priority attributed. As far as the group in the EP was concerned, he demanded to get ready not as much for an Ocean Pact, but an Ocean ACT. He listed the areas in which he was expecting particular efforts for a credible action oriented agenda:

- enforcement of existing legislation;

- review of the Marine Framework Directive in order to place stronger emphasis on adopting an ecosystem approach everywhere;

- more decisive efforts to decarbonise maritime traffic, where European owned companies were major players;

- get 20% of renewable energy from the ocean;

- equal protection of workers in maritime industries across all of Europe.

In his brief welcome statement, Starfish Mission Chair Pascal Lamy placed all the emphasis on the need to learn and communicate broadly about the resources and ecosystems under the water surface.

In his brief welcome statement, Starfish Mission Chair Pascal Lamy placed all the emphasis on the need to learn and communicate broadly about the resources and ecosystems under the water surface.

In the political arena his principal demand was to get all members of the European Commission together behind an impactful Ocean Pact.

Four panel sessions covered a lot of ground throughout the day, though presentations dominated the agenda, leaving discussions almost exclusively to networking breaks.

It started out with ‘Ocean Health, Productivity and Resilience’.

Monica Verbeek, Executive Director of Seas At Risk, recalled the commitment to achieve 30% protection of ocean spaces with emphasis on doing better than the largely nominal marine parks declared on paper, but hardly enforced. As much as possible these spaces should become strictly protected to restore a tired ocean to a healthy state again. She also cautioned that such protection should not be interpreted by imply that 70% of the ocean could continue to be mismanaged. Instead, 100 of the ocean and adjacent land areas should be restored too and achieve good environmental status. That would mean to finally implement and enforce the Marine Framework Directive, so that the benefits would accrue to marine ecosystems and all citizens.

Monica Verbeek, Executive Director of Seas At Risk, recalled the commitment to achieve 30% protection of ocean spaces with emphasis on doing better than the largely nominal marine parks declared on paper, but hardly enforced. As much as possible these spaces should become strictly protected to restore a tired ocean to a healthy state again. She also cautioned that such protection should not be interpreted by imply that 70% of the ocean could continue to be mismanaged. Instead, 100 of the ocean and adjacent land areas should be restored too and achieve good environmental status. That would mean to finally implement and enforce the Marine Framework Directive, so that the benefits would accrue to marine ecosystems and all citizens.

There were many areas, including renewable energy from the ocean and cleaning up toxic port environments, which required a concerted efforts. The necessary funding should come from an Ocean Fund which could be well-endowed by cutting harmful subsidies. She passionately argued for a ban on bottom trawling, particularly in so-called Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), where all destructive activities should be off limits. Instead, curbing plastic pollution and regenerating fish populations should provide healthy and nutritious seafood most of which should not have travelled half the globe to reach our plates.

Joachim Hjeri, founder of Havhǿst in Denmark, argued in favour of putting regeneration at the heart of all interaction with the ocean. Just reducing the level of harm of ongoing activities while pursuing a logic of short-term profit was inacceptable and would prevent reaching the restoration objectives. He cited several examples of civil society initiatives, where citizens were practising e.g. low trophic level aquaculture (rather than unsustainable high trophic salmon fattening) and other regenerative activities. The challenge was, of course, first to scale down industrial-scale use with many negative side effects, then to scale up and scale out successful citizen initiatives and inspire others to take similar action adapted to their context. Blue gardens were a case in point, which doubled up as incubators for local entrepreneurship and support for small-scale fishers. The diversification of activities provided valuable learning spaces that were low risk, but helped to identify what worked and what didn’t.

Sylvain Blouet, Deputy Director of the Marine Protected Area Côte Aganthoise in France, cautioned that involving citizens step-by-step in developing, monitoring and enforcing protective measures took time. Building the trust necessary to create readiness for behavioural change was a rather intensive process involving regular interaction that underpinned collective learning. It was important to engage with the professionals, but also recreational ocean users and politicians. The use of mediators was highly recommended to facilitate the co-construction of understanding and management measures. Maintaining trust and engagement required continuous effort. It was advisable also to engage with the education system to ensure longer-term continuity as well as nurturing partnerships with research.

Sylvain Blouet also emphasised the importance of continuity in finance. In their case, an 8-year LIFE project had provided essential planning and management security. More engagement of the private sector was an area needing more attention, while local ecotaxes could perhaps also become a source of financial support. Small financial or other incentives warranted thought to encourage nature friendly practices.