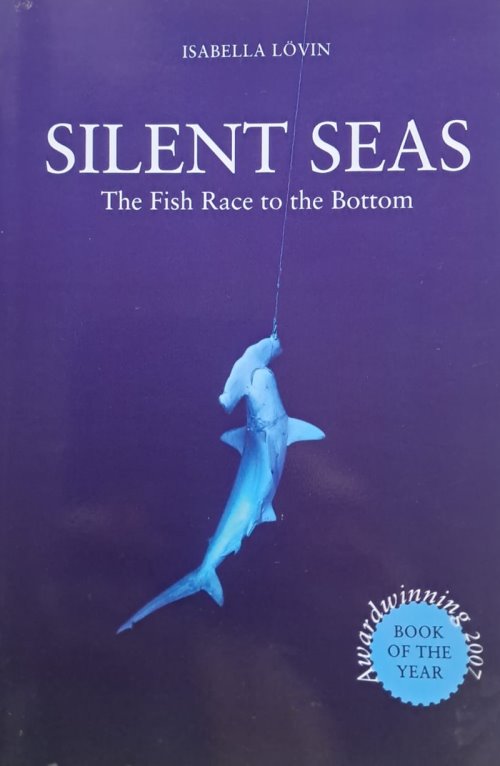

Isabella Lövin, 2012. Silent Seas – The Fish Race to the Bottom. Paragon Publishing, 244 p. Swedish original 2007. Tyst hav – Jakten på den sista matfisken, Ordfront – The English language edition has been updated.

The title of Isabella Lövin’s book “Silent Seas”, obviously refers to the ground-breaking classical book by Rachel Carson “Silent Spring” from 1962. And for good reasons. Just as Carson saw the danger of a future with much less birds, less wildlife in general and degraded ecosystems on land, so does Isabella Lövin fear a future of seas and lakes with much less fishing, less wildlife, ecosystems dominated by species on lower trophic levels, such as blue green algae, which we do not appreciate that much. Both Carson and Lövin were shocked by the outcome of careful research on what was going on in the environment and the poor performance of the authorities set to protect it. The extremely careful accounts of the situation in both books are impossible to reject. It is only typical and regretful that the books have almost 50 years between them. The situation under water has been neglected much longer – just because we cannot see it, or perhaps because many waters do not have a responsible owner.

Isabella Lövin at a lunch debate at the ULB in 2014

Isabella Lövin is the journalist specialising in environment, who became EU parliamentarian. The way from the first to the second started with research for a newspaper article on eel fishing in Sweden. The first dramatic chapter of the book tells us about how she attended a seminar about eel fishing in Stockholm, where apparently everyone from researchers, authorities to the fishers’ association knew about the precarious situation for the eel and thus eel fishing. About 99 % of the eel in Sweden was gone. The situation in all of Europe was alarming. Understanding reproduction of the eel, in fact a quite mysterious fish, was mostly lacking. The participants at the seminar argued that private eel fishing had to be forbidden, but how to protect commercial eel fishing? At this point the young journalist Lövin stands up to ask “Why do you not declare eel a protected species? It would be the natural conclusion for almost any other animal.” Silence. It was painfully clear that protection of the environment and biodiversity was a secondary concern. Protecting the sector and the jobs was number one.

The rest of the book tells us about a long series of conflicts between those concerned with long-term protection of the waters and the fish, and the short-term commercial interests. Cod fishing has a central place since it was and is in danger in the Baltic Sea and even worse on the Swedish West coast. It seems like the Swedes or the Europeans in general did not learn anything from the collapse of the world’s most spectacular and rich cod fishing in Newfoundland and outside Cape Cod (sic!) on the American East coast. The cod in the Baltic Sea, as well as elsewhere, was no match to the extreme technological development of the fishing methods with sonars, large trawls, and freezing equipment on ever larger ships. While the fish populations shrink, the fishing industry is illogically provided with endless subsidies to invest in new and larger ships and equipment to be able to catch increasing amounts of fish – which simply do not exist. One of the shocking details in Lövin’s book is that the Swedish government’s investments in the fishing sector – everything from fossil fuel subsidies to salaries when not allowed to fish – is almost exactly the same, 1 billion SEK, as the economic value of the entire commercial fishing sector. For the state (and for taxpayers) it is a zero sum game.

The actors in this drama are all portrayed personally, with names and backgrounds and all. Some – almost all – should be ashamed of what we learn from their self presentation and publicly available information about them.

The drama itself is strange: The authorities see themselves as mediators running a negotiation between one part, the fishing industry, and the other, the scientists. The scientists have the job to keep track of the fish populations and often to recommend a sustainable level of fishing quotas, necessarily small or even zero. The fishing industry, which want to have income enough to be able to pay their loans for ships and equipment, needs to fish and thanks to sophisticated equipment knows where the fish is, even if it is the last survivors of a population. The authorities after having been pushed over and over again by the commercial interests decide on fishing quotas far above the recommended, which the fisheries will not reach and which will end with the collapse of the fish population. The circular thinking of both industry and sector authority is shocking.

The drama itself is strange: The authorities see themselves as mediators running a negotiation between one part, the fishing industry, and the other, the scientists. The scientists have the job to keep track of the fish populations and often to recommend a sustainable level of fishing quotas, necessarily small or even zero. The fishing industry, which want to have income enough to be able to pay their loans for ships and equipment, needs to fish and thanks to sophisticated equipment knows where the fish is, even if it is the last survivors of a population. The authorities after having been pushed over and over again by the commercial interests decide on fishing quotas far above the recommended, which the fisheries will not reach and which will end with the collapse of the fish population. The circular thinking of both industry and sector authority is shocking.

Why do the sector authorities not see themselves as representing the citizens and tax payers of the country? Why do they feel obliged to allow the industry certain “fishing rights”, with or without the help of researchers even though it is clear for everybody that they are allocating a rapidly shrinking cake instead of (re)building a bigger one?

On land this would be more obvious. Why is it not on the sea? Isabella Lövin asks several of the key people during her travel in order to understand this institutionalised folly. They all refer to being compelled, even though sometimes they are ashamed for failing to protect and at least maintain the resource, or even more so the ecosystems, the environment, biological basic conditions.

The story begins with Lövin’s examination of the Swedish conditions, but continues in Brussels and at the European Union level. Sweden is bad enough, but the European level looks even worse, if nothing else for its bigger size. The EU is the largest fishing “nation” in the world and the largest consumer market of fish, 70% of which is currently imported because of dwindling, overfished domestic resources. The same flawed logic and mismanagement applies. The consequence is that European fishing fleets, oversized for their domestic waters and dominated by Spaniards, now have moved to and contribute to emptying the seas around Africa and Latin America. The seas are becoming silent there as well. And especially the poor nations in Africa are the losers after having signed contracts with the EU that are unfavourable to them. Of course, some of the Asian and Russian fleets may be even more aggressive in their exploitation of African waters, but that is no justification for the EU to spend taxpayers’ money on unsustainable practices.

Reading Isabella Lövin’s book Silent Sea is like reading a detective story. We ask ourselves how it will end, who is the culprit? She takes us to all these environments, from government offices to the ships (with seasickness), where the crime is committed. She talks to the old fishermen who remember old times when overfishing was not a problem. She also talks to the scientists who explain the changes that have occurred in the ecosystems few people know about, but which are the most dramatic consequences of sustained overfishing. At the end, it is clear who the victim is – the fish! Though something else also becomes clear: no fish in the water, no fishing. It’s like spending your bank account instead of living off the interest.

Legal minimum size of cod (Gadus morhua) in the North Sea is 35 cm, but the biological minimum is twice that!

After the publication of the book and very much as a consequence of her shocking findings, Lövin started a carrier in politics. Soon afterwards, she was elected a member of the European Parliament for the Swedish Green Party. Not only is she one of the best-informed politicians on the fishing policy issues, she has also been able to achieve quite a lot. The conditions for the seas in 2013 and 2014 are a little bit better than in 2007, when the book was published in Swedish. At the time of writing the review, a number of positive steps have been voted in the reform process of the European Common Fisheries Policy. Overfishing is now illegal. The big battle now is to implement the political reform at EU level and particularly in every single EU Member State bordering the sea.

The last chapter in the book is a discussion of possible actions to improve the dire situation of Swedish and European seas. Some are particularly effective and worthwhile:

-

Establishing marine protected areas (no-fish zones, where the fish are allowed to reproduce and rebuild their abundance).

-

Freeing research on fish populations from the oversight by sector administrations and entrusting it to independent universities (to make the data and their interpretation independent of short-term commercial interests).

Yet others are well known and in need of implementation:

-

Police the fishing vessels more effectively – today about 20 % of fishing in Scandinavian waters is illegal;

-

Make destructive bottom trawling illegal;

-

Outlaw discarding (dumping) of fish.

Others have already had some effect, such as labelling fish to make the origin transparent in the shops, though the level of fraud in some fisheries has undone some of the positive effects.

The fishing policy of a country and the EU, financed by tax money, should obviously be there to secure good fish for all citizens and protect a living marine environment for the current and future generations, not serve narrow and destructive interests of a small group at the expense of all others.

The realities are still the opposite, in Sweden, in Europe and, indeed, in much of the world. It has to be changed. Isabella Lövin’s book is a good step towards achieving that and put the natural resource question back into the centre where it belongs: into public stewardship, not backroom dealing. It should be read by all citizens, particularly those who have already a voluntary or professional role in this development. The book is a good guide to understanding the issues for what they are, political in nature and dependent on functioning democratic institutions. They are certainly not mere technical matters, though a lot of knowledge about nature and technicalities of the trade are not only helpful but even warranted. Let us hope the book will be as influential for the rebuilding of healthy oceans as Carson’s book was for taking the measure of the crisis on land.

Lars Rydén

Centre for Sustainable Development

Uppsala University

24 March 2014