Paul Treguer’s Neptune in Trouble

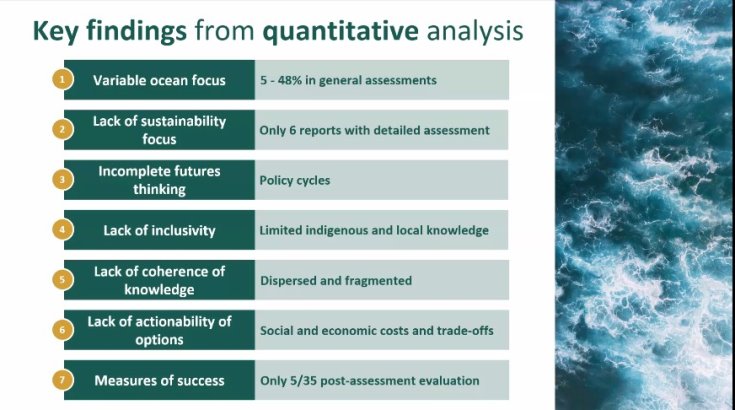

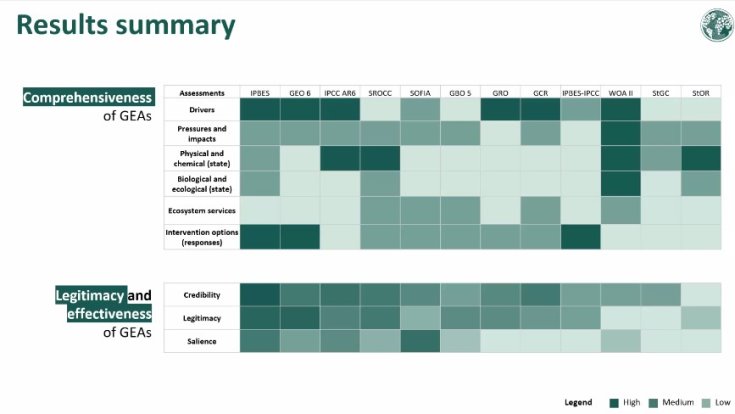

The ocean is under siege from multiple human activities. Recognised as global commons, the One Ocean Summit in Brest, France, in 2022 marked its ascendence on the global political agenda. The second UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon last year called for the establishment of an International Panel for Ocean Sustainability (IPOS) in order to replace technocratic and fragmented approaches towards the ocean by more comprehensive, transdisciplinary, more inclusive understanding and a much improved science-policy interface to help deliver on Sustainable Development Goal 14 ‚Life Under Water‘. Following the invitation of the EU Council, the European Commission (DG MARE) commissioned the Seascape Assessment, to demonstrate the feasibility of the IPOS. This event organised on 15 November 2023 at the European Parliament was an opportunity to present the results of this assessment. It also allowed to discuss the need, vision and key objectives to improve the interface between science and policy for the ocean, as well as the links between IPOS and the EU’s International Ocean Governance agenda. Guests included members of the European Commission, MEPs, politicians, scientists and practitioners. The Seascape Assessment looked at 35 global studies screening them with 77 criteria in eight categories. It came up with interesting insights as to three broad categories influencing their ability to inform policy processes: their comprehensiveness, their legitimacy in the eyes of policy makers and the effectiveness of the messages. The analysis of the global studies was complemented by semistructured interviews around 25 questions to gauge engagement with ocean issues and guidance to inform the positioning of a future IPOS. Finally a number of multi-stakeholder workshops aimed at co-creation led to six potential configurations for IPOS.

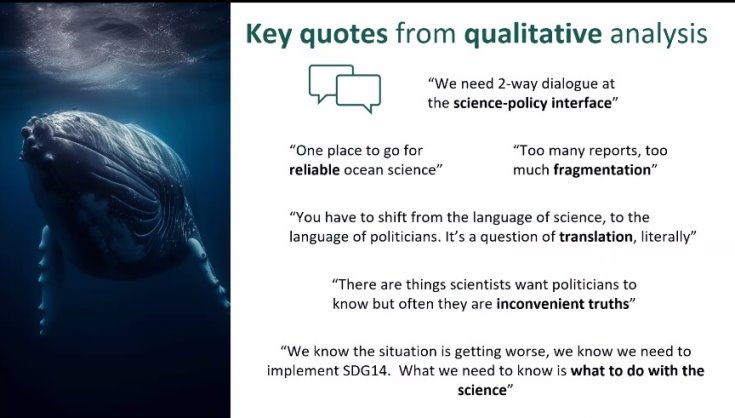

Comparatively few reports covered ocean issues in any depth. Key findings were a lack of inclusivity and that even reports with thorough analyses were weak on how to translate their findings into potential actions that could be considered in policy negotiations. Analyses of social and economic costs and benefits and areas of trade-offs were often underdeveloped or absent. This was also reflected in the qualitative analysis as illustrated in some key quotes below. Clearly, working in silos was a major obstacle to bringing much needed very diverse knowledge and experience to bear on solutions.

The summary table below shows how the major reports score in comparison. It suggests that indeed there is a need for a more comprehensive, inclusive and action oriented panel focused on ocean sustainability. Ambassador Olivier Poivre d’Arbor, Special Envoy of the French Republic’s President for the UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, in 2025, expects that the establishment of an IPOS will be one of two scientific deliverables of UNOC3. He thinks that the cryosphere will play an important role in ocean reporting as the dramatic collapse of ice sheets around the poles will affect one in every ten people in coastal zones and the retreat of mountain glaciers will affect the water supply of 2 billion people very directly in the next few decades. He pledged support for a United Nations Decade on Polar and Glacier Sciences 2025 to 2034 and said the science must deliver important inputs for diplomacy to address the associated threats.

During the debate among several other speakers, Brian O’Riordan, Senior Adviser of LIFE, the platform of small-scale fisheries organisations in Europe, cautioned that a dedicated mechanism would be needed to ensure meaningful interaction between IPOS and small-scale fisheries and indigenous communities if inclusiveness was to be taken seriously. Geneviève Pons, Director General and Vice President of Europe Jacques Delors Centre, invited participants to focus on cooperation and continuous exchange while keeping an eye on vested interests and national interests. She cautioned that State representatives could be sensitive to vested interests affecting their economy or political landscape. She explained that the typical tactics to prevent change was to cite one institute not in agreement with majority science as had been seen in the battles about glyphosate, other agriculture policy issues and e.g. difficulties to agree on marine protected areas, not only paper parks. She believed that agreeing on global metrics to assess temperature increase, acidification and sealevel rise was important to get civil society everywhere on board and that it was essential to then translate the findings into international and national commitments and agreements that could then be monitored, by researchers, politicians and civil society. Food for thought on the road to UNOC3 in 2025 and beyond. Click here for the institutional report.