Darwin Year – 2009 – to commemorate two centuries since his birth and his links to the sea

The young man

During a visit in Cambridge, UK, in September 2009, the town reverberated with events in the occasion of the Darwin Year commemorating his 200th birthday. Countless public and academic events had already taken place and more is still to come. Christ College has lots of illustrated material on its website in honur of its illustrious student. All photos by C.E. Nauen.

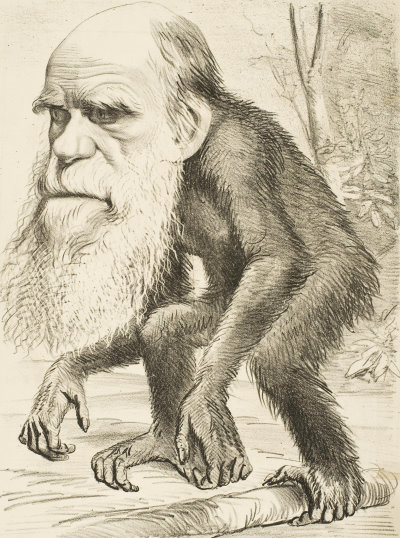

Charles Darwin (CD) was born on 12 February 1809 in Shrewsbury at ‘The Mount’ to Susanna Wedgwood, daughter of the potter Josiah Wedgwood, and Robert Waring Darwin, a physician. As his father wanted him initially to become a physician as well, he entered Edinburgh University in 1825. According to his autobiography, he was not particularly enthralled by his studies there and repeated in much of the abundant literature about him. Yet he learnt a lot about the science of his day from his mentor Dr. Robert Grant, an early scholar of evolution. It was here that he was introduced to principles of collecting and dissecting and classification, including marine organisms, a mainstay of science then. It was under the guidance of Grant that he dissected a lumpfish and wrote up his first scientific write-up, which already revealed his keen observation and grasp of the relationship between observed facts and scientific theory.

Another forming experience was his relationship with John Edmonton, «a former South American slave of African ancestry established in Edinburgh, from whom CD took private lessons in taxidermy… it appears to have opened his mind to respecting people outside his narrow class and ethnic background, thus enabling him to learn from the people he met in his later travels and readings, and, ultimately, to formulate a theory that encompassed all of humanity, and embedded us within the same nature. This contrasts with the divisive schemes propagated by less open-minded contemporaries, e.g. Louis Agassiz and Richard Ower, whose religious prejudices, combined with social opportunism, ultimately undermined their science.» (D. Pauly, p. xviii, Darwin’s Fishes – see below).

After two years his father realised that Charles did not want to be a physician and accepted an alternative career of clergyman for his son, conditional on taking at least a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree from a university.

His grandfather and his cousin, Hensleigh Wedgwood, had both attended St. John’s College in Cambridge, while Darwin’s older brother Erasmus had already graduated in 1828 with a medical degree from Christ College. Moreover, William Darwin Fox, a second cousin and lifelong friend, was also a Christ’s. So the family’s connections to Cambridge University were well established.

Introduced by William Darwin Fox to Prof. John Stevens Henslow (1796-1861), Charles befriended Henslow and attended his botanical lectures. The two became good friends to the point, that Darwin was known as ‘the man who walks with Henslow’.

From an early age, CD was keen on angling, an activity he pursued with great interest and dedication into his travelling years.

He also developed a passion for beetle collection and learnt about geology from Adam Sedgwick (1745-1873). Darwin was so fond of collecting beetles that he got a special cabinet made for his collection, here shown to the right with a net to catch insects.

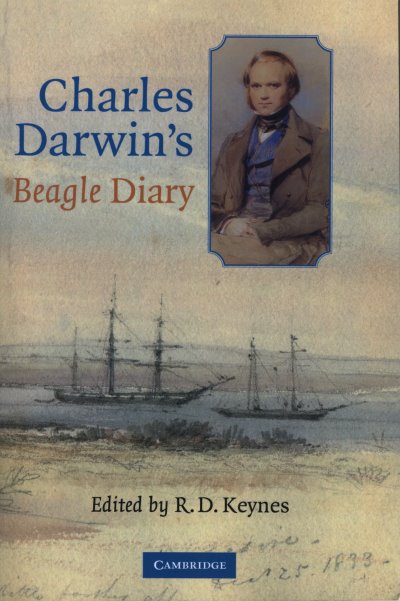

It was Henslow, who recommended that the young Charles accompany Captain Robert FitzRoy on the surveying journey of HMS Beagle around the world.

Christ College, one of the oldest Cambridge Colleges, founded in 1505 by Lady Margaret Beaufort, kept its doors open for a Darwin tour for much of 2009. Darwin spent two and a half years (from November 1829 to June 1831) in the First Court at Christ College.

As a young man from a wealthy family, Charles was a ‘Pensioner’, a student with private means occupying spacious quarters, which are today reserved for a lecturer. The room has been restored based on research into historic fabrics found in the room, correspondence and contextual knowledge about the period.

At the time heating was through the fireplace and illumination was through rapeseed oil lamps and wax or tallow candles. Gas lamps arrived only later in the century. Today, it looks like this.

Darwin passed his B.A. exams on 22 January 1831, but remained at Cambridge until the summer. It was during this period that he read about scientific travel by Alexander von Humboldt, a long-time inspiration for his own work and travel.

The invitation to join the voyage of the Beagle reached him while he was geologising in Wales. His father’s initial opposition almost prevented it all from happening, but thanks to the good arguments of his cousin, Josiah Hedgwood II, his father consented and after an initial false start due to very bad weather, the party took off from Plymouth on 27 December 1831.

The young man that had the position of gentleman naturalist and geologist on HMS Beagle and company for captain Robert FitzRoy was not the Charles Darwin we now commemorate. Yet, he was a relentless worker, busying himself with observations, collections and experiments – very much in the mould of a modern scientists rather than following only in the footsteps of the classics. It was all about finding out and testing rather than devoutly referring to the ancients.

The sculpture of the young Charles by Anthony Smith is now permanently located in the Darwin Garden of Christ College. It was unveiled on Darwin’s 200th birthday, 12 February 2009.

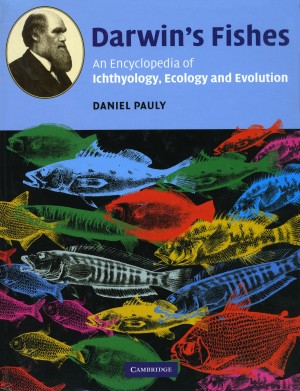

Thursday 12th February 2009: To mark Charles Darwin’s 200th birthday Dr Daniel Pauly, Professor of Fisheries at the University of British Columbia and a world expert on fish conservation, opened Darwin’s Fishes, the major exhibition of the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Iinstitution’s (BRLSI) 2009 Darwin and Beyond programme.

Thursday 12th February 2009: To mark Charles Darwin’s 200th birthday Dr Daniel Pauly, Professor of Fisheries at the University of British Columbia and a world expert on fish conservation, opened Darwin’s Fishes, the major exhibition of the Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Iinstitution’s (BRLSI) 2009 Darwin and Beyond programme.