Claire Weeda of Leiden University opened the Symposium

The symposium hosted by the University of Leiden cast the net widely on different aspects of managing and using natural resources in the pre-industrial Low Countries always marked by their relationship to the marshy delta of the Rhine, the Meuse and other rivers. The relatively young ‘discipline’ of environmental humanities blends approaches using written sources typical of the historical methods with archeological investigations and sources from geology, biology, hydrology and more. Claire Weeda of the University of Leiden opened the symposium.

This gathering invited to look both at the natural environment and its biodiversity and the institutions governing access to them, including early requirements to cope with extreme events. The researchers highlighted a widespread attitude of risk reduction and avoidance of constructions in flood plains while also investing into drainage to gain space for agriculture. Some case studies allowed glimpses into the hard life in those days, but also how segments in society were striving to safeguard and improve their conditions and the role of institutions demanding collaboration for the common good, often in contrast to the privileges of church and civil potentates.

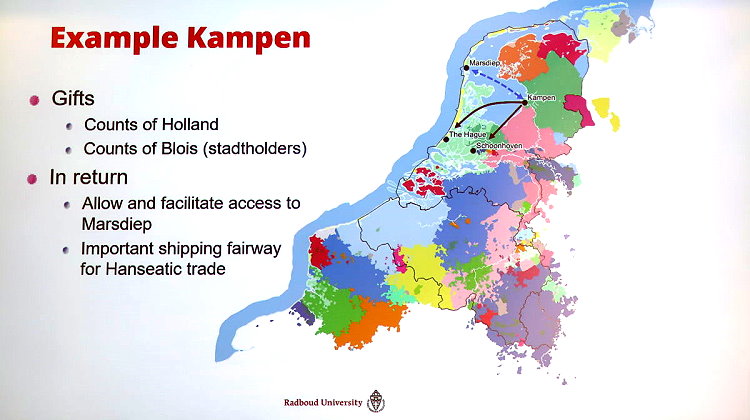

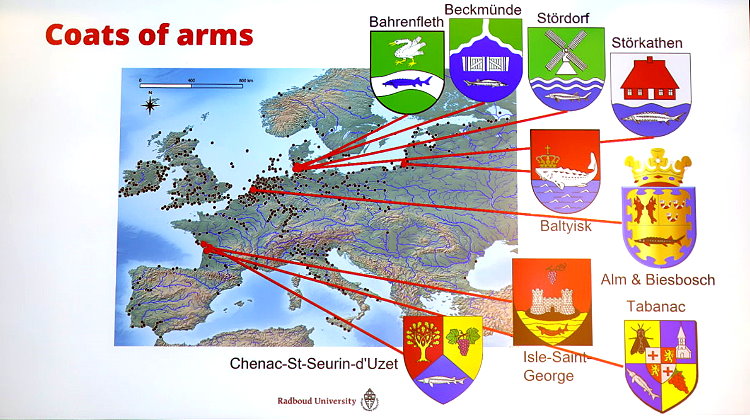

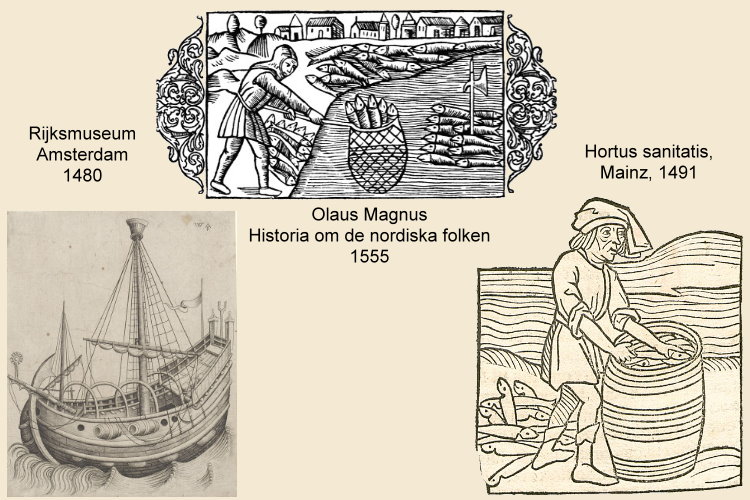

Rob Lenders of Radboud University Nijmegen reported on the specialised fisheries for sturgeon as a source of wealth particularly for the city of Kampen. Catches, allowed sizes and marketing channels were highly regulated for this symbol of power at the banquets of the rich. Sales were only allowed during two days after capture.

Most catches were destined as gifts to civil and church authorities in exchange for privileges and rights e.g. access to the outer islands for more efficient participation in the trade of the Hanse network. The fish would sometimes be transported alive for relatively short distances by horse cart, usually accompanied by a cook, who could preserve the precious cargo in vinegar should it not survive.

In the discussions the question arose over and over as to whether these medieval societies could hold lessons of sustainable living with nature for modern times. Clearly the commons of land, water, living resources on land and in the water played a bigger role in providing sustenance compared with private appropriation of a few or of externalising pollution effects by types of production influenced by few on all others as in modern times. But obviously the population was orders of magnitude smaller than today and did not have the technical means many of us take for granted.

The highlight of the symposium was the keynote address of Richard C. Hoffmann of York University, Canada who summarised key messages from his recently published book ‘The catch’.

Richard C. Hoffmann of York University delivering his keynote address

He outlined how ‘ecological revolutions’ or what we would today call ‘regime shifts’ typically occur when the accumulation of many individual actions and processes unintentionally reach a critical point and quantity spawns a new quality. It’s what the US economist Alfred E. Kahn called ‘the tyranny of small decisions’

Between the 6th and the early 13th century fisheries were essentially local and for subsistence. As Christian culture banned eating meat for certain periods, fish became an accepted substitute.

Demand beyond fishing communities increased and led to the gradual creation of markets and some early incidents of local shortages. By about 1500 three major changes emerged:

- Aquaculture of common carp – originally confined to the Danube river system, it spread west- and northward into regions which were warm enough for at least three months of the year in the 17th century to ensure the survival of the juveniles of this rather hardy species as adults.

- Flemish herring fishery, the Almadraba bluefin tuna fishery around Cádiz, and the fishery of coalfish fishery (Pollachius pollachius), all expanding the frontiers of fish marketing and consumption thanks to preservation techniques: brined herring, dried tuna, head-off pollack.

- Early recreational fishing, first documented at the end of the 14th century, was an entertainment for courtly parties of the elite, giving rise to a new concept of ‘licit play’ provided it was pursued with moderation (Giacomo della Marca, 1391-1476). Fish became a human artefact.

What started as a subsistence activity over centuries, through the ‘tyranny of small decisions’, became first an increasing mechanised activity during early industrialisation supporting population increases, and, most recently one of the ‘hockey stick curves’ of amazing technological prowess with the role-out of fossil fuels and military technologies after WWII. Welcome to the anthropocene.

See the full programme here. Text and photos by Cornelia E. Nauen.