MEPs Isabella Lövin, Luke Ming Flanagan, and Emma Fourreau hosted the meeting ‘Make Fishing Fair’ organised by Low Impact Fishers of Europe (LIFE) and Blue Ventures in the European Parliament on 25 March 2025.

This event brought together small-scale fishers, Members of the European Parliament, European Commission officials, Permanent Representatives of EU Member States and key stakeholders to discuss fairer access to fisheries resources. Event highlights included:

- Rebalancing quotas – the case for Article 17

- Small-scale fishers speak out – real stories from across Europe

- What’s next? MEPs & DG MARE on future action

Other Europarliamentarians speaking were Paulo do Nascimento Cabral, Eric Sargiacomo, and Emma Fourreau, as well as Ana Miranda briefly on specific problems in Galicia. Acting Head of Division D/3 Eoin Mac Aoidh commented for the European Commission’s DG MARE.

Isabella Lövin recalled some of the difficult consultation and negotiation processes that led to the reform of the European Common Fisheries Policy (CFP). Key questions were how much can we take out while maintaining the resources and the entire ecosystem in a healthy state? And who would have the right to fish? Many who considered marine resources a public good opposed individual transferable quota rightly fearing that their introduction would quickly lead to a significant concentration of power as witnessed e.g. in Denmark and Iceland. Art. 17 was adopted to enable a broader range of sustainability criteria to guide quota allocation, but only 16 of 27 Member States provide indications as to what criteria they use for such allocation among national interest groups once the European-wide quota were established for each country at the annual ministerial meeting before X-mas.

Paulo do Nascimento Cabral & Eric Sargiacomo

Paulo do Nascimento Cabral reported that the Portuguese government delegated most of the tuna management in the Azores sector of the EEZ, representing 85% of the quota, to the Azores government. Fishing restrictions have been adopted such as minimum landing size and maximum landings to protect the spawning stock. He doubted the usefulness of the annual ministerial EU process and argued instead for extending true protection to declared marine protected areas to allow rebuilding of stocks and give room to co-management with other stakeholders to have a broader view of how the sector was developing or which direction to take in the face of other influences such as increased tourism, climate change and more. Ensuring broad technical and political consensus was essential for the ability to act.

Eric Sargiacomo also criticised the allocation of fishing rights on the basis of past catches as this prevented the generational renewal. The ongoing review of the CFP showed already that the current sector governance had not produced the expected results. It was imperative to move towards a more inclusive model of governance and use social, economic and ecological criteria for better stewardship.

The ensuing complaints of small-scale fishers about the blatant lack of implementation of the CFP then centered on what that meant in practice. Article 17 of the CFP stipulates that ‘When allocating the fishing opportunities available to them, as referred to in Article 16, Member States shall use transparent and objective criteria including those of an environmental, social and economic nature’. Twelve years after the entering into force of the reformed CFP the small-scale fishers remain at a fundamental disadvantage in quota allocation that EU member states confer almost entirely to industrial fishing companies.

Gwen Pennarun

Marta Cavallé at the helm of LIFE illustrated this eloquently at the opening supported by a video showing some of the ground realities of small-scale fishers. She denounced that Member States were systematically attributing fishing rights to those with the greatest responsibility for the poor state of resources. Marta asked insistently to make sure, that this structural injustice be ended and small-scale fishers be recognised and promoted as the more environmentally and socially benign producers of quality seafood.

Gwen Pennarum, a Britanny line fisher, described how the monopoly granted to a few big companies to the lucrative tuna fishery left no economic space for coastal fishers. In the face of high investment for new boats meeting licencing requirements it had become almost impossible for young fishers to enter the profession in replacement of older fishers retiring. In the absence of decisions bringing the national policy in line with the CFP requirements for transparency and a broader basis beyond past fishing quantities the numbers of small scale fishers, though still numerically the vast majority, were steadily declining. He thus asked for an equitable repartition of fishing quota to correct this downward spiral of concentration of dwindling resources under the control of fewer industrial interests.

Seamus Bonner of the Irish Islands Marine Resource Organisation (IIMRO) characterised the challenges its members were facing. IIMRO is a co-operative representative group, fisheries producer organisation based on the offshore islands of Ireland and is working to preserve and promote sustainable fisheries for its members. Boats are only about eight meters long crewed by one to three fishers catching high value species like lobster with passive gears like pots. They are developing a host of initiatives to decarbonise fishing, make seafood traceable for consumers and holding on to traditions that have been recognised by UNESCO as intangible cultural heritage. Their demands are:

- remove the track record of past catches from quota allocations and use sustainability criteria;

- allocate ring-fenced quota to local communities;

- standardise this application of the CFP across the EU to end arbitrary variation in national policies;

- provide guidance towards such application and on public reporting for transparency

- act on the resolution of the European Parliament (2021/2168(INI))

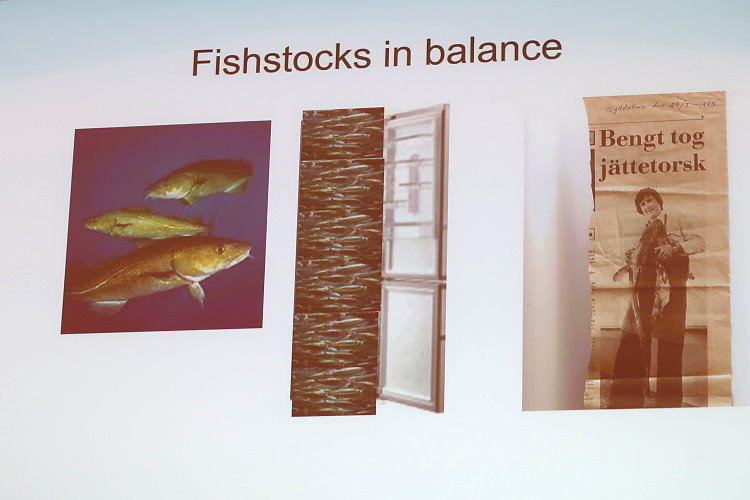

Bengt Larsson, the leader of Swedish small-scale fishers (Sveriges Yrkesfiskares Ekonomiska Förening, SYEF) and LIFE board member, illustrated the dramatic changes that have taken place during his life time. Given the dramatic overfishing of cod that led to the fishing ban for the species in 2019, he gave up what he called ‘offshore’ fishing with his 10 m long steel boat. The same is the case for herring, some 90% of which was nowadays caught by industrial fishing for fishmeal for Norwegian salmon cage culture while wild salmon was starving and in bad shape as a result. He had turned to inshore fishing with his 6 m boat where the big trawlers could not go. He was now fishing perch, pike, whitefish and other inshore species. 30 years back the major fishing season was from January to March, it was now down to two weeks because there were so few fish in the water. After huge catches in the 1980s the first signs of declining populations were visible to fishers already in the 1990s, but the mostly industrial overexploitation went on relentlessly.

Bengt Larsson in 1985 with a big cod. His version of a balanced ecosystem shows a few big cod as top predators in balance with a large population of herring as major prey species.

He concluded his account with an appeal to

- give priority to low impact fishing

- limit the machine power of trawlers to max. 600hp to reduce fishing pressure

- base management measures on consideration for the entire ecosystem to rebuild biomasses and restore at least a resemblance of balance in the Baltic ecosystem

- apply Art. 17 in full

- re-allocate subsidies to research.

Eoin Mac Aoidh of DG MARE responded by affirming that the Commission recognised small-scale fishers as valuable actors in the sector and noted that a third of the fisheries fund goes to SSF. He acknowledged that in the absence of shared definitions and baselines Member States were interpreting Art 17 in different ways in relation to the meaning of the criteria and transparency requirements. The Scientific Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF) is investigating that to inform improvements. However, fishers should have ‘realistic expectations’ as the Commission had no power over the way Member States were allocating quota, but planned to issue a Vade mecum for application of the rules in a more harmonised manner. Having ring-fenced allocations to SSF was out of the question.

The Commission could not propose or even impose a binding implementation plan that would stop the decline of the small-scale fleet.

The Commission could not propose or even impose a binding implementation plan that would stop the decline of the small-scale fleet.

That was a cold shower for the audience. In one of the few questions from the audience for which was still time, Christian Tsangarides, LIFE BANS coordinator, thus asked what sort of reality this debate about improved CFP was about. It had raised much hope, but many other countries had effectively moved forward and had some results in rebuilding resources, while the EU was badly falling behind. There was an obvious discrepancy between declarations of things getting better because of good management when catches in European waters were falling. The way measures were applied on the ground constituted as a matter of fact an incentive for less selective gears with high bycatch. This undermined the landing obligation de facto completely.

The frustration was palpable. Words, no action to stem the decline.

Isabella Lövin

With that the focus on Art. 17 was seemingly not the most effective way to heal the damage of not applying the CFP in good faith. But Isabella Lövin reminded the audience that the mandate to rebuild the stocks to a level higher than what could produce the maximum sustainable yield was still unfulfilled and required action. Recovery could be achieved by fishing less across the board, let the ecosystem rebuild to healthy levels. That would enable to harvest more with less fuel and effort.

She touched a critical point. As the research team around Rainer Froese of GEOMAR in Kiel had shown already 10 years ago that a production increase of five million tons per year from European waters would be possible if catches of juveniles were stopped and biomasses of spawning adults were allowed to increase. EuroStat documented instead declines of recorded landings of fisheries products from European waters from about 6 million tons in 2001 to 3.2 million tons in 2022 (1). The question in the Baltic is now even whether cod can bounce back at all.

So it’s time to apply the law and its provisions for real, not waste more precious years breaking the rules for political expediency and to please the lobbies of industrial destruction of ocean and public health. One may reason that in such a scenario of moving from paper parks to strongly protected areas and overall reduction of fishing effort, small-scale fishers had probably lesser economic pressure from interest payments to service loans for very high capital investments than industrial fleets. That could make the transition easier to manage with some help. But they will need to have some assurance that they get also the benefits of any further sacrifices they should make.

Emma Fourreau made a passionate final plea for fairness. It will require a lot more public pressure in EU Member States not to be lost in lengthy procedures with little impact on the ground. Many citizens appreciate stewardship of small-scale fishers and want declared protected areas to be strongly enforced. A good starting point would also be to ensure respect of exclusion zones for trawlers in coastal waters reserved for small-scale fishers. The exact rules vary from one country to the next, however, coastal fishers complain almost everywhere about lack of action by coast guards against trawler incursions. Let the citizen speak out more strongly and hold elected representatives and administrations accountable.

(1) Eurostat. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?oldid=583760

Summary account by Cornelia E Nauen

Académie de la pêche artisanale

- Make Fishing Fair in the EU, 25 March 2025

- Relations entre l’Homme et la biodiversité au travers de différentes échelles

- Célébration de la Journée mondiale de la pêche au Nigeria, 21 novembre 2024

- Mundus maris a participé à la Journée mondiale de la pêche 2024 organisée par la Canoe and Fishing Gear Association of Ghana (CaFGOAG).

- Contribution de Mundus maris à la consultation publique de l’UNOC3

- Sommet sur la pêche artisanale à Rome, 5-7 juillet 2024

- Symposium régional sur la pêche artisanale européenne, Larnaca, Chypre, 1-3 juillet 2024

- Réunion d’urgence sur la pêche dans la Baltique, Bruxelles, 26 juin 2024

- Ambivalent role of Market and Technology in the Transitions from Vulnerability to Viability: Nexus in Senegal SSF

- Shell fisheries as stewardship for mangroves

- Edition Africaine du 4ème Congrès Mondial de la Pêche Artisanale (4WSFC) à Cape Town, du 21 au 23 novembre 2022

- Journée mondiale de la pêche, 21 novembre 2023

- Séminaire en ligne : Défis et opportunités de la pêche au Nigeria

- Présentation de l’application FishBase au Symposium de Tervuren

- Conférence MARE sur la Peur bleue – Mundus maris réfléchit

- The Transition From Vulnerability to Viability Through Illuminating Hidden Harvests, 26 May 2023

- Les sessions de l’EGU se concentrent sur la géoéthique et l’apprentissage collaboratif

- Solidarité avec les artisans pêcheurs du Sénégal et de la Mauritanie

- The legal instruments for the development of sustainable small-scale fisheries governance in Nigeria, 31 March 2023

- Tools for Gender Analysis: Understanding Vulnerability and Empowerment, 17 February 2023

- Community resilience: A framework for non-traditional field research, 27 January 2023

- Sustainability at scale – V2V November webinar

- 4WSFC Europe à Malte, 12-14 septembre 2022

- Mundus maris prend part au Sommet de Rome consacré à la pêche artisanale

- Women fish traders in Yoff and Hann, Senegal, victims or shapers of their destiny?

- L’Académie continue son travail à Yoff

- Illuminating the Hidden Harvest – a snapshot

- Virtual launch event FAO: International Year of Artisanal Fisheries and Aquaculture

- The Small-Scale Fisheries Academy as a source of operational support to PA Guidelines

- World Fisheries Congress, Adelaide, 20-24 September

- Mundus maris supports the fight of Paolo, the fisher, in Tuscany, Italy

- Rattrapage – Academy PAD à Yoff, 27 févr. 2021

- Renforcement des capacités des acteurs de la pêche artisanale

- Essai des méthodes de formation lors de la phase pilote de l’Académie PAD au Sénégal

- Une première – Inauguration d’une Académie de la pêche artisanale au Sénégal