As part of the preparations for the next global small-scale fisheries congress, regional gatherings are convened by the research platform ‘Too Big To Ignore’ (TBTI) and its partners under the suggestive title ‘Bright spots – Hope spots’. The one for Europe gathered a small group of researchers and fishers near Larnaca, Cyprus, from 1 to 3 July 2024. Katia Frangoudes based at IUEM/UBO, Brest, France was the principal host not sparing any effort to make the meeting professionally productive in the lovely atmosphere created by traditional Cypriot hospitality.

Katia and Ratana Chuenpagdee of TBTI Global were the co-chairs of this symposium that offered excellent opportunities for more in-depth exchanges than normally afforded by big conferences which allow only 10 to 12 minutes presentations and hardly any Q&A time outside of coffee breaks and socials.

Two interesting new books were presented, both also available as affordable e-books: José Pascual Fernández of the Universidad de La Laguna, Spain, introduced the consolidated version of a broad panorama view of European small-scale fisheries he had edited together with Cristina Pita and Maarten Bavinck and which had been published in the MARE Springer series; and Julia Nakamura of the Legal Office of FAO presented the latest book in the series titled ‘Implementation of the Small-Scale Fisheries Guidelines. A legal and policy scan’, co-edited by Ratana Chuenpagdee and Svein Jentoft.

Cornelia Nauen presenting (Photo courtesy Katia Frangoudes)

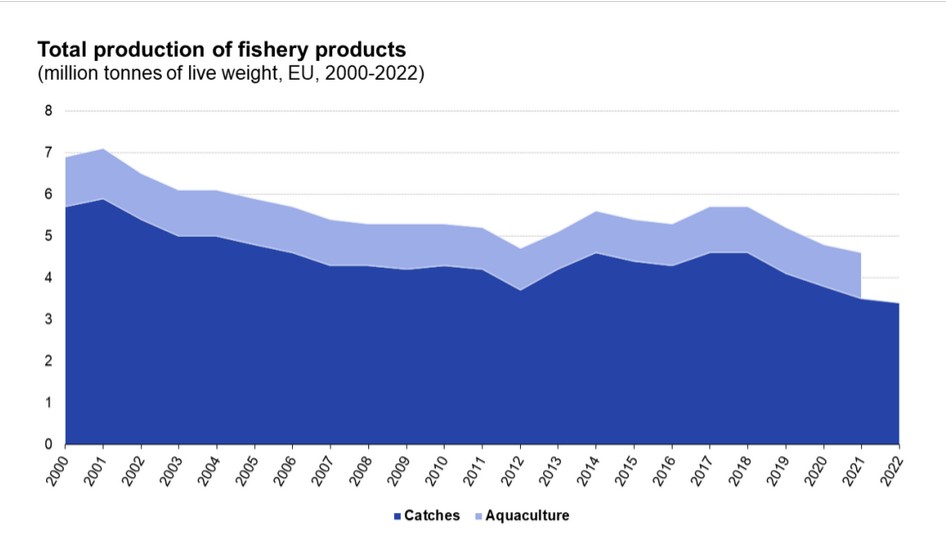

Cornelia E Nauen of Mundus maris presented two hope spots against the backdrop of falling total production in European waters, though the value of the production is up in inflationary mode, due to a combination of scarcity, higher production costs and profits, particularly in long value chains.

According to the European Commission, the socio-economic importance of small-scale fisheries (SSF) in European waters can be summarised in a few key figures: 74% of the fleet, though only 8% of the tonnage, most vessels are in the size group of between 5 and 7 m length over all (loa), 3 GT, with a 34 kW engine. In 2021, the SSF fleet accounted for 49% of sector employment, but more than 50% in regions which are most dependent on fisheries. Value of landings with 12% of the total exceeds landed quantities of around 7%. Gears most in use are trammel nets, traps, hook and line and longlines with low environmental impact.

One case presented focused on the Initiative ‘Casa dei Pesci‘ along the coast in Tuscany, Italy, spear-headed by a courageous artisanal fisher, Paolo Fanciulli. A large following of scientists, tourists, local authorities and all kinds of civil society and company representatives brought together swarm intelligence to find creative approaches against long-term overfishing only temporarily interrupted by WWII. Overfishing is not a new phenomenon in the Mediterranean as it was even lamented in Roman times, where the appetite for fish in the capital city could only be satisfied by imports from the provinces.

For some time, the coast guard and other public services in charge of maritime activities were not keen to enforce the 12 mile coastal exclusion zone countries can reserve for SSF and keep out high-impact bottom trawling. Bottom trawling counts as industrial fishing in the European legislation pertaining to public subsidies, no matter the size of the vessel. The attitude is changing gradually as awareness about the environmental damage of certain forms of industrial fishing is growing. And the economics of trawling a shrinking resource makes it increasingly unattractive and may become a stronger driver than appealing to rational insights and environmentally and socially responsible business strategies.

Paolo Fanciulli at the pier in Talamone, summer 2021

Environmental awareness has certainly grown, not the least as a result of pescatourism Paolo Fanciulli gained official acceptance for in Italy. His small vessel ‘Sirena’ can take up to 12 people per day. During the summer season, day in day out, for more than 10 years, he would tell them the story of his life-long struggle in defence of marine life and the former Posidonia habitats and show them the freshness of fish caught in the trammel nets no longer than 1000 m set the night before.

Those trips grew the community of supporters and triggered many original and creative protection measures. The most spectacular one consists of enticing renowned sculptors to carve out marble blocks from the Michelangelo quarry in Carrara into statues. The marble blocks were donated by the owner of the quarry after accompanying Paolo on one of his trips. Emily Young and other sculptors put all their artistry into the project of an underwater museum that created new habitat and prevented bottom trawling in the process.

The measurement of a small sample of fish caught in Paolo Fanciulli’s nets last year shows that most specimens are big enough to reproduce and thus help the ecosystem recovery.

The diversification of economic activities, including running a restaurant in his garden in the evenings based on a menu with freshly caught fish is hard work to survive in a context, where resources are too scarce and market access too difficult as a single basis to feed the family. This is the fate of many other fishers like him, so long as protective measures are not in place on a larger scale to rebuild the productivity of the ecosystem. These protective measures are all the more urgent as the rapidly warming surface waters will become attractive to more and more species migrating into the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. This Lessepsian migration, named after the builder of the Suez Canal, takes place increasingly rapidly in counter-clockwise direction from the Eastern Med, reaching already into the lower part of the Adriatic. Lionfish (Pterois volitans) and Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus) are only the tip of the ‘iceberg’ and happen also to be marketable species. This is not the case for the poisonous silver-cheeked toadfish (Lagocephalus sceleratus) a badly invasive species of puffer fish that can grow to monstrous sizes of one meter or more in the Eastern Mediterranean, where it inflicts damage of local fisheries by destroying nets and eating fish caught on longlines. So far, more than 660 exotic species originating in the Indo-Pacific and Red Sea have been identified in the Eastern Mediterranean, replacing gradually the local fauna.

Michalis Croessmann speaking at the first SSF Summit in Rome, September 2022

The second case study presented concerns the initiative of the Association of Commercial Fishers on the Island of Amorgos, the most eastern Greek island in the Cyclades archipelago, headed by Michalis Croessmann. He and his fellow coastal fishers realised that unless they took action against overfishing and massive plastic pollution, they would be the last of their kind.

And they did act. In 2021 they started stopping any fishing during the major spawning season of their target species in April / May and used that time not only for maintenance etc., but half of the members of the association also went out to collect garbage from the beaches around the island, many of which were only accessible from the sea.

In the first two years of this initiative, the fishers collected more than 1200 large bags of litter, plus many very big items. They sent more than 15 tons of plastic for processing, where 60-65% will be recycled. They also recycled more than three tons of fishing nets and ropes, something that made them think about how to change their own equipment to either be easier to recover in case of loss or being naturally recyclable. The support of two environmental foundations was crucial for this success.

While initially unsuccessful in getting European funding for their initiative, the national ministry accepted to endorse a year-long biological study of the resources around the island, co-funded by the NGOs. It also approves of the joint proposal of the fishers and scientists discussed at length leading to a strategic five-year plan for Amorgos. The plan envisages three no-take areas applicable to all fishing and a temporary stop fishing stop around Amorgos for all fishers, irrespective of their home port during the spawning season. This is already respected by most fishers. It is recognised that the fishers need compensation for the loss of fishing opportunities when collecting plastic garbage. Otherwise, the economic hardship would spell their demise. Thanks to increasing media coverage and persistent work of the fishers and the coalition supporting then, the need for resource recovery is rapidly gaining public acceptance. During the recent ‘Our Ocean’ Conference in April 2024 in Athens, the prime minister announced a ban on bottom trawling in Greece with potential for achieving greater scale. Both cases are small-scale compared to the urgent need to rebuild lost ecosystem functions and productivity on a much broader front. Both have male fishers as main protagonists, but women strongly supporting, whether in the family business, as researchers or at the helm of supportive civil society organisations. The extent to which they will be emulated for larger impact will depend on whether the public authorities, encouraged also be wide-spread public support, will engage more strongly in favour of nature protection and shifting priorities away from industrial fishing interests towards low-impact coastal fishing creating employment and added value to local economies. The greatest encouragement for the SSF is when they become again attractive enough for the younger generation to see a future in living of responible fishing. The slides are available here.

A typical catch dominated by lionfish with a mix of local and exotic species delivered for pooled trading

A particularly noteworthy part of the symposium consisted of a visit to the Larnaca SSF landing sites in the vicinity and an afternoon session featuring a conversation between local fishers and their peers from the UK. During the visit of the landing site two fishers explained how fishers try to eke out a living by outsmarting food competitors like dolphins, trying out modifications of fishing techniques and grouping together for better market prices thanks to delivering to the same marketer in Zygi they trust and thus command better access thanks to larger quantities. Naturally there are institutional differences affecting the coastal fisheries in the two countries. Possibly the biggest difference is that there is still some fish to be had for the UK coastal fishers. That generates respectable annual income, though the fishers had to cope with significant losses due to direct competition of a small fleet of industrial vessels with super-large surround nets taking an entire school of herring or mackerel in one go. Such a school would have provided coastal fishers with catch and income for a year or more. Altogether their general status as fishers in public opinion has suffered as a result of greater awareness of damage done by industrials.

Will (speaking) and Barry from the UK explain the loss of status of SSF in the UK, but still get by

In Cyprus, the local resource base has all but collapsed and what little catches they can land is often dominated by exotic species, such as lionfish, as here to the right. At least lionfish is delicious both grilled and fried, but the poisonous spines need to be carefully removed before processing. Catching shrimp which command high prices requires small mesh sizes and can generate unwanted by-catch of juveniles of commercial species, thus compromising future harvests. A public programme paying fishers 4.8€ for every kilo of poisonous silver-cheeked toadfish landed towards incineration provides some economic relief.

Ilias and Photis, the two outspoken fishers receiving symposium participants at the port and joining the meeting for the remainder of the day regret that the government is not listening to their plight and suggestions even though they are better organised than in some other countries. They think it’s a missed opportunity for finding better answers to the seemingly unstoppable decline.

Still, they did not want to give up. Antonis was mandated to take a message of hope and also defiance to the SSF Summit scheduled in Rome immediately afterwards.

Two Cypriot fishers joined the conversation, Ilias (left) and Photis (middle) sitting next to Antonis Petrou often serving as consultant to support SSF in Cyprus

There are no easy solutions, but in several cases discussed during the symposium the future looked bleak. It will require strenuous efforts to rebuild the resources of a functioning ecosystem to counter the combined effects of invasive species in an overfished system and various effects of climate change already felt strongly. Such efforts need modifications in policies from local to European levels, together with more trust-building between government institutions, fishers and other stakeholders. Beware of the suggestions for technology fixes, which will often provide only temporary respite without addressing the fundamentals. Only too often, higher investment into technologies will create indebtedness and force fishers – as is happening in other natural resource sectors, such as agriculture – to push the ecosystem even harder to repay their debt, reducing the chances for a robust recovery in the process. It enriches the technology firm owners and the banks, but usually ruins particularly small-scale operators.

The balancing act between multiple demands on space and resources, which are often competing directly, would benefit from more systematic dialogue hearing all voices, including those of environmental and social scientists, and not only those of wealthy investors. This is not at all a mere fancy, but a proven way to minimise harm from ever more conflictual situations, both for nature and for societies, from local to national. That requires adequate policies aimed at keeping societies out of harm’s way. Stopping the bullies that put their own short-term gains over everything and everybody else is crucial for livable futures. That is a collective responsibility for current and future generations. Where such inclusive dialogues are in place, solutions respecting planetary boundaries are being carried forward through broad consensus.

Photis returning from a fishing trip |

Small Lagocephalus sceleratus |

|---|---|

Typical coastal fishing boat |

Larnaca fishing port |

Cutting spines off a lionfish |

Delicious lionfish fried and braised offered by Photis to participants |

The detailed Symposium programme with abstracts of papers presented is available here.

All photos by CE Nauen, unless indicated otherwise.