Upon the invitation of the Faculty of Economics of Coimbra University in Portugal, Mundus maris President, Dr. Cornelia E Nauen, was invited to give a lecture titled ‘Environmental negotiations and the rule of science and NGOs’. In the warmth of the spring day, almost all 100 students of Prof. Licinia Simão’s course on diplomacy cramped into the lecture hall.

Photo courtesy: Licinia Simão

The lecture traced some concepts and approaches from the wave making book ‘The Limits to Growth’ by Donella Meadows of MIT and co-authors published by the Club of Rome in 1972, and the proposed alternative published in 1974 by the Bariloche Foundation group of researchers, led by Amílcar Herrera in Argentina, who challenged the neo-Malthusian assumptions of the MIT model. Instead, the group put forward a Latin American World Model (LAWM) based on the principle of meeting basic needs for all and discouraging consumerism instead.

Through a series of UN conferences understanding of the brewing environment crises, social injustices and fears of wider food insecurity evolved step by step. While not accepted by all states, the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment influenced many concepts and ideas in the following decades. At the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, better known as the Rio Earth Summit, the prevailing mindset was still to pitch economic development against the environment. In the event 150 signed up to the principle of meeting basic needs for all. It ended with three non-binding political documents

- the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development

- Agenda 21

- Forest Principles

and, more importantly, with three legally binding conventions with large adherence:

- the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), was signed by 168 states until June 1993 and entered into force in December 1993 after the 30th ratification. As of today it has 196 countries as parties to the Convention after their ratification.

- the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) entered into force in March 1994. 198 countries ratified the text and are parties to the Convention. The 2015 Paris Agreement supersedes the UNFCCC’s Kyoto Protocol signed in 1997 for a period from 2005 to 2020. The protocol was based on the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities.

- the International Negotiating Committee set up for preparing the UN Convention to Combat Desertification. This convention entered into force in 1995 after receiving 50 ratifications.

Researchers and non-governmental organisations were prominent participants in the negotiation processes leading up to these international agreements and closely accompany their monitoring and further development since by contributing during and before and after the annual Conferences of the Parties (COPs) particularly of the CBD, the UNFCCC, and later negotiations.

The UN Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012, colloquially known as Rio +20, was the third international conference on sustainable development aimed at reconciling the economic and environmental goals of the global community. Rio+20 was a also a follow-up to the 10th anniversary of the 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg.

Yet, the ground realities were more in line with the MIT model heading for disaster as a result of overexploitation of natural resources and continued injustices to billions of people in supposedly developing countries. Many activities in capitalistic production and consumption modes were not grounded in the ‘meeting basic needs’ principle.

The successive reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) synthesising the best available research results in the most relevant areas, including the economic costs of climate change impacts, and by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) established by States to strengthen the science-policy interface for biodiversity and ecosystem services for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, long-term human well-being and sustainable development are influential for the public debate. Even when governments do not follow the advice the results of these studies and assessments are used e.g. by civil society organisations to push for more climate and biodiversity protection action. Indeed, many CSOs use research results actively in translating them into more directly policy relevant formats, something the science policy briefs have also started to deliver [1] [2].

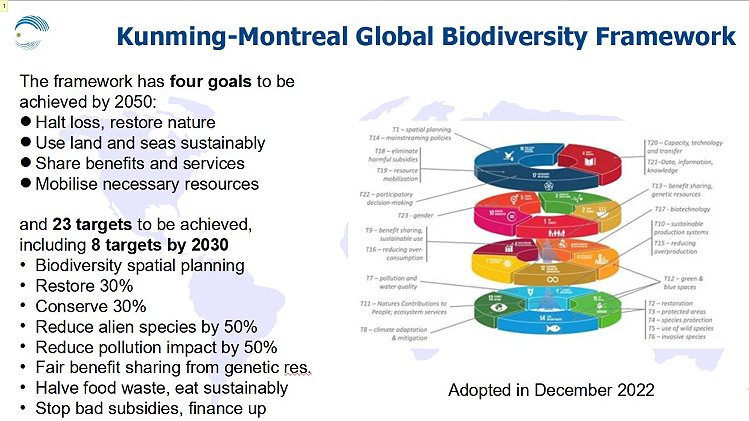

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KMGBF or simply GBF) is a major development under CBD to take action against widespread species extinctions. In the ocean, fisheries is a major driver. This is why protecting and rehabilitating 30% of the ocean (and the degraded land) by 2030 (the 30×30 objective) is a core element of the agreement completed in December 2022 and now in the process of ratification to enter into force as fast as possible. Time is of the essence as only full protection can create the hoped for benefits for people and ecosystems as Mark Costello pointed out during the EU Ocean Days 2025 based on an extensive review of the literature.

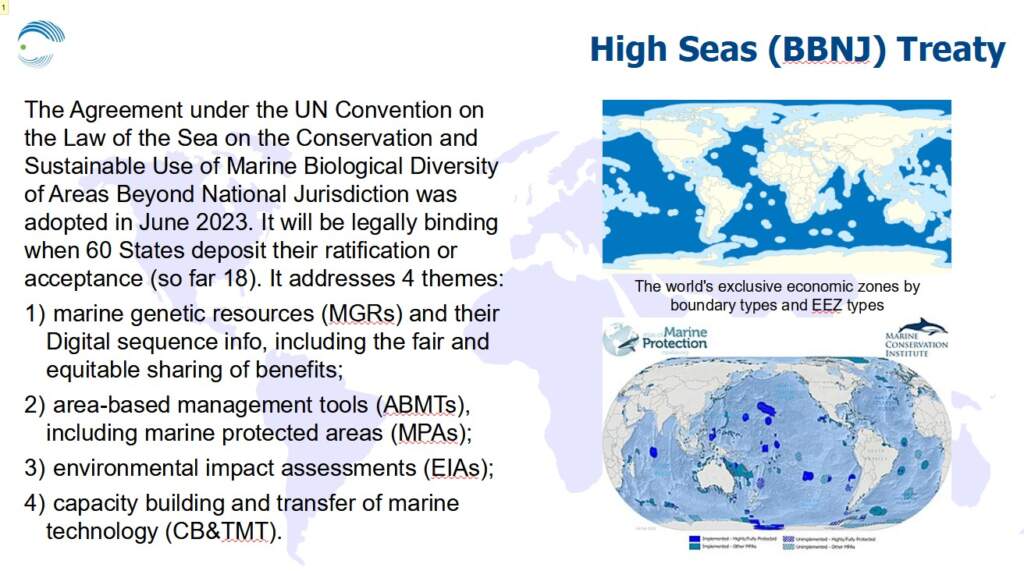

After almost 20 years of negotiation another treaty was agreed on biodiversity in 2023, this time under the Law of the Sea with a focus to protect biodiversity in areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ or High Seas Treaty), an enormous part of the global ocean not governed systematically by any rules and left to exploit by the few countries and companies with the technical means to do so. The High Seas Treaty enhances the chances to reach the 30×30 objective. It comes with commitments for fair benefit sharing of marine genetic resources of importance to medical research and the cosmetic industries, among others, and capacity strengthening for developing countries.

Spain is the first European country to have ratified the agreement and the pressure is on to use the great opportunity of the third UN Ocean Conference (UNOC3) co-hosted by France and Costa Rica in Nice, France, from 9 to 13 June 2025 for a big splash because the BBNJ has at least 60 ratifications of states to enter into force.

UNOC has been created in 2017 to end the homelessness of the ocean on the political agenda even though it is the biggest connected ecosystem on the planet and intimately influences both the climate and biodiversity. Given that 90% of all internationally traded goods, currently 11 billion tons/year or about 1.5 tons per living person, it is also of utmost importance for the social and economic justice challenges humanity faces. So, fittingly, this year’s UN motto for World Ocean Day 2025 on 8 June is ‘WONDER – Sustaining what sustains us’.

Environment-Negotiations_Science_NGOs  What are some take-home messages?

What are some take-home messages?

- Trust building and dialogue are crucial to break the internationally negotiated principles down to local context and make them work. Dialogue and deliberations to achieve an agreed goal work best in a safe space where everyone is respected and accepted without judgement.

- Civil society organisations therefore need to use invaluable research results from all areas of knowledge to help access to others while respecting other forms of knowledge such as those held by practitioners like small-scale fishers, indigenous groups and others.

- Foremost, it is important to organise in groups around important objectives of social fairness and nature healing and protection. Cooperate! Make sure, nobody is left isolated and more prone to be targeted by violence of those seeking power and profits no matter what. Peaceful, but firm, cooperation and collective action can achieve great and fair solutions.

The slides of the lecture are available here.

The visit at the Economics Faculty (FEUC) was also the pleasant occasion to sign a Memorandum of Understanding between the FEUC and Mundus maris with a focus on developing academic, scientific and cultural cooperation with a focus on ocean policies, international ocean governance, and environmental diplomacy.

José Manuel Mendes, Dean of the Economics Faculty, Cornelia E Nauen, Mundus maris, and Licinia Simão, Deputy Dean; Foto by Luis Serrano (FEUC)

[2] IPBES (2019): Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. S. Díaz, J. Settele, E. S. Brondízio, H. T. Ngo, M. Guèze, J. Agard, A. Arneth, P. Balvanera, K. A. Brauman, S. H. M. Butchart, K. M. A. Chan, L. A. Garibaldi, K. Ichii, J. Liu, S. M. Subramanian, G. F. Midgley, P. Miloslavich, Z. Molnár, D. Obura, A. Pfaff, S. Polasky, A. Purvis, J. Razzaque, B. Reyers, R. Roy Chowdhury, Y. J. Shin, I. J. Visseren-Hamakers, K. J. Willis, and C. N. Zayas (eds.). IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany. 56 pages. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3553579