The conferences for young marine researchers (YOUMARES) of the German Society for Marine Research (DGM) started as a self-organised event to give students and young professionals an opportunity to share their study results, gain experience in presenting their work in a friendly environment and network. Over the years participation grew more and more international and since the pandemic the general shift towards hybrid events allowing remote participation opened up new opportunities. The on-site part of the 14th edition was convened in Hamburg on board the museum and entertainment ship Cap San Diego, in close proximity to the emblematic concert halls of the Elbphilharmonie.

The conferences for young marine researchers (YOUMARES) of the German Society for Marine Research (DGM) started as a self-organised event to give students and young professionals an opportunity to share their study results, gain experience in presenting their work in a friendly environment and network. Over the years participation grew more and more international and since the pandemic the general shift towards hybrid events allowing remote participation opened up new opportunities. The on-site part of the 14th edition was convened in Hamburg on board the museum and entertainment ship Cap San Diego, in close proximity to the emblematic concert halls of the Elbphilharmonie.

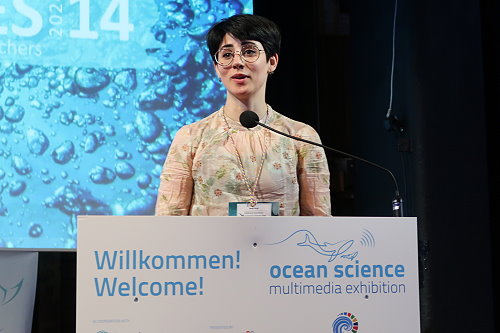

The key organiser and master of ceremony of several sessions was PhD researcher Deniz Vural, who with her excellent sense of professional organisation in combination with considerable charme managed to get the three day event off the ground and to a successful closure, from 15 to 17 May 2024. As we have seen ourselves in several occasions it can be challenging to obtain timely feedback and delivery on all promises from people in diverse circumstances and sometimes struggling with their own constraints. So Deniz deserves the unreserved respect and appreciation of all participants and contributors to the conference and its stimulating side events.

Talking about side events. It all started out with a great opportunity to visit the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea located in Hamburg since 1996. YOUMARES participants were treated to an informative, at times even awe-inspiring, presentation and walk-around by press officer Julia Ritter. The Tribunal will be delivering on 21 May 2024 a much awaited Advisory Opinion upon the request from Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law. It felt like being close to when history is written.

Monica Facci of Mundus maris introduces the background and scope of the role play on protecting biodiversity during the Ocean Forum

Mundus maris attended with intern Monica Facci and president Cornelia E Nauen to test the role play developed over the period of Monica’s internship around the challenge of simulating the often difficult deliberations between diverse stakeholders around making a marine protected area work in practice. The background is straight forward: the huge concern about what has been termed the ‘Sixth Mass Extinction of Species’ has led to the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework at the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in December 2022. The massive loss of biodiversity on land and in the sea is threatening to disrupt the many goods and services humans take from nature, including food production and public health. Establishing and managing not only the expansion of marine protected areas (MPAs) to 30% of the sea, but also doing better on the other 70% together with a host of other measures constitutes a very ambitious roadmap for change. MPAs have been declared in about 10% of coastal seas in recent years, but a study published in Marine Policy in 2023 suggests that the vast majority are mere ‘paper parks’.

On day two the volunteers of the first day slipped fast into the exchange as they had had time to familiarise with their characters

So moving from almost 10% paper parks to 30% spaces with real protection covering all types of habitat is a stark order. And we know that such measures are only feasible, if a broad social consensus is achieved at least across many, if not all, stakeholders. And what to do about those minorities with deep pockets and a lot of political influence who seem not to care about common goods for all, if in words but not in deeds? Are we all prepared to stand up for the commons ordinary people need so much to exist and thrive? Do we all listen carefully to the discourses of different groups and engage in respectful dialogue to distinguish between genuine information and fakes? Do we have the courage to weigh arguments also in terms of who needs more support and who has already a lot and can carry a greater burden of change to enable biodiversity protection for all?

At the Ocean Forum on day one of the conference, Monica explained the background and scope of the role play. She explained the intense preparation with a good number of interviews of a range of stakeholders in and outside of Europe and extensive literature research to sketch the different characters that represent groups of people or organisations with an intense interest in MPAs because these can affect their work and living conditions. Monica further explained that the play would put forward a ficticious scenario of a soon to be declared MPA.

Ad hoc group of participants interested in the role play as they study their characters already seated in an open circle

She invited participants to imagine slipping into the shoes of one of these characters and engage with others in the search for enough common ground to make the MPA work and achieve the restoration and protection objectives. Up to eleven roles were offered, each with an information sheet to facilitate impersonating the representatives as follows: artisanal fisher, natural scientist, director of the future MPA, head of a marine conservation organisation, public official (mayor), owner of a tourism organisation, representative of an offshore wind park investor, representative of the local sewage plant, a fisher woman, an industrial fisher (captain), a social scientist. For reasons of schedule, the play itself was to be done the following day after volunteers had chosen their roles. A moderator was to facilitate the deliberation, keep time and make sure the exchange remained respectful and focused.

During the rather too short slot for the role play, participants sat in an open circle getting quickly into trading arguments pro and con of the MPA. While everybody had a chance to speak up the time was too short to come to a meaningful consensus. Some characters turned out to be more dominant than others. Overall the consensus-seeking was stronger than taking a stance against very determined opposition from the industrial fisher. He plainly denied that there was any overfishing and stated that the MPA was unnecessary and an unwelcome burocratic obstacle to his ife already made difficult through excessive regulations and controls. In this group, appeasement attempts prevailed without coming to a conclusion.

The ad hoc group quickly got into the exchange with the mayor (yellow shirt) taking a front seat to steer the direction

As the group started their role play, other conference participants spontaneously voiced their interest in setting up another discussion group quickly chosing a character of their liking. Naturally, they first needed to read the related information sheets and thus started with a little delay to present their respective role to each other. Here the mayor took on a more proactive role in his desire to position the town and its surroundings as an attractive ‘green / blue’ investment place. Arguments were traded between the tourism company and the industrial fisher and the offshore wind farm pretending to occupy part of the planned MPA. The investment into better sewage treatment needed some further explanation but was then positively judged. Shortly before the time was up the moderator sought to fathom how far apart the positions still were and whether all parties could agree (a) to acknowledge the need for an MPA and (b) agree that at least the most critical area with the spawning grounds should be a no-take area. That seemed to be acceptable for a clearly needed second round of the deliberation.

Because of the conference scheduling the much needed debriefing could only be set up during the last day when some participants had already left the venue. The feedback was nevertheless very helpful to review the material before sharing it with the groups in different places interested in using the role play for World Ocean Day (8 June) celebrations. The strongest advice was to confer a sense how tough it can be to counter the arguments and influence behind the scenes of big investors or entrenched industry groups can be. So the search for consensus may need to focus more on those stakeholders who depend more directly on a healthy ocean and to put limits on accommodating those sometimes openly destructive interventions. Otherwise, one may end up with a paper park with no real restoration and protection effect for biodiversity and the marine habitats. The debriefing showed that citizens, small-scale fishers, conservationists and companies building their business on a heathy ocean need to be a lot more articulate and organised to achieve the goal. One participant also suggeted that the future park director could take over the moderation role as a way to make the scenario more realistic.

Because of the conference scheduling the much needed debriefing could only be set up during the last day when some participants had already left the venue. The feedback was nevertheless very helpful to review the material before sharing it with the groups in different places interested in using the role play for World Ocean Day (8 June) celebrations. The strongest advice was to confer a sense how tough it can be to counter the arguments and influence behind the scenes of big investors or entrenched industry groups can be. So the search for consensus may need to focus more on those stakeholders who depend more directly on a healthy ocean and to put limits on accommodating those sometimes openly destructive interventions. Otherwise, one may end up with a paper park with no real restoration and protection effect for biodiversity and the marine habitats. The debriefing showed that citizens, small-scale fishers, conservationists and companies building their business on a heathy ocean need to be a lot more articulate and organised to achieve the goal. One participant also suggeted that the future park director could take over the moderation role as a way to make the scenario more realistic.

The Mundus maris team is grateful for the feedback and hopes to collect even more from the next test runs as a way to provide a learning ground for becoming the nature saving change we all need. Please contact us at info(at)mundusmaris.org if you want to help refining and finalising the instructions for a fun learning experience.